Under the Radar, Issue 27

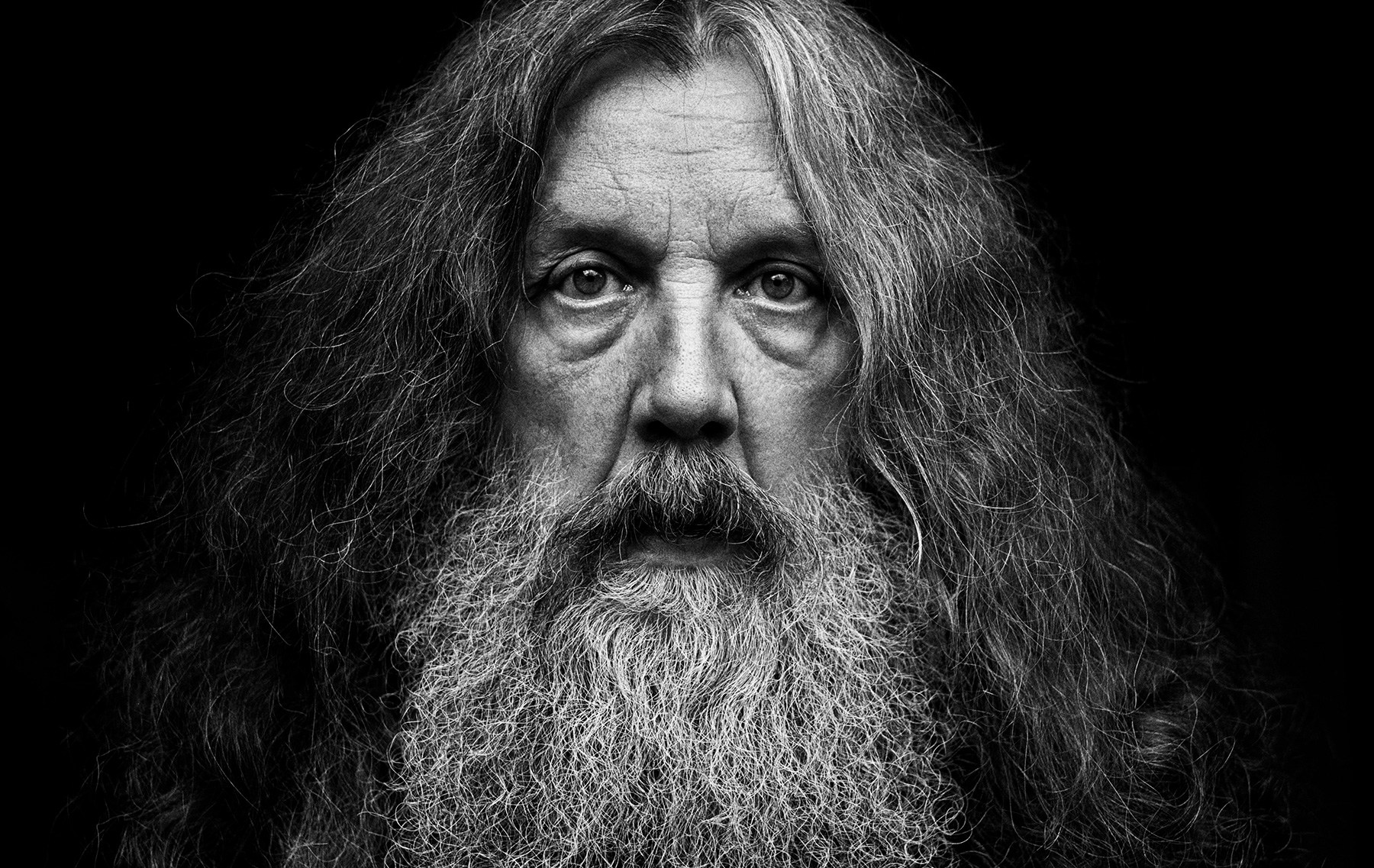

In his home in Northampton, England, Alan Moore is sitting in what he calls "the position I spend most of my life"—that is, in front of his computer, a device he is quick to confess has been relegated to the function of a glorified electric typewriter. Though it is not by intention, the 55-year-old is something of an imposing figure. Whether it is the assortment of rings on his fingers or his wild hair and beard, it's little wonder why people who have only seen pictures of the man assume he is someone to approach with caution.

When Moore speaks, however, these misconceptions of some odd and eccentric artist are replaced with that of a modern-day Merlin, someone whose words, spoken in a lower register, are not only quite rational, but also intelligent, eloquent, and, at times, said with plain-spoken humor. "People think I'm a lot weirder than I actually am," says Moore. "It's just I'm in a very weird world."

Over the course of 25 years, the world Moore occupied was composed primarily of multi-dimensional heroes and villains whose stories have made him one of the most respected and critically lauded writers of the comic book genre. From the annotated historical research in his Jack the Ripper tale, From Hell, to the dystopian politics and moral ambiguity of V for Vendetta, to the deconstruction of the very superheroes and vigilantes he embraced within perhaps his greatest work, Watchmen, he approached the storytelling of a paneled narrative differently than anyone else who came before him.

Nowadays, Moore has almost completely divorced himself from the trade that established his career, thanks in large part to the strained relationship he held with his former publishers at DC Comics. While he admits to keeping a certain level of familiarity with the medium, Moore says he hasn't even read a comic book for quite some time. "I hear about stuff that's happening," he says, "and I'm sure there are some very good books out there. But there are none that to me seem to be pushing things forward in the way I was interested."

Moore's concern for comics becomes even less enthusiastic when the element of Hollywood is involved, particularly if it implicates his own work, and Moore famously has no interest in viewing film adaptations of his comics, including the recent Watchmen movie. "I get the impression that [comic] creators—if they got the offer of some big Hollywood money—would think of the film as being the pinnacle of the process, and that if those film people want to completely change my comic, well that's OK because they're more important than us. There's more money in films than comics, so therefore they must be more important. Those are not the values that I make decisions upon. I tend to look at what the film industry is capable of and what my comics are capable of, and I come away with the conclusion that my comics are of a much higher technology. We were able to accomplish stuff in a 1980s comic book—which consisted of eight folded pieces of paper and some ink-that was really elegant and coherent, perfectly themed, perfectly designed, that Hollywood, with all of its money, cannot do successfully."

These days Moore has been focusing his creative energy elsewhere, most notably in his novel Jerusalem (the spiritual follow-up to Voice of the Fire). He is also writing in collaboration with his friend and mentor, Steve Moore, a referential grimoire entitled The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic, a text of occult history, theory, and instruction.

Yet despite all his posturing that the comic book industry has lost its innovation and greater integrity, Moore cannot turn his back on one of his favorite creations, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Developed by Moore and artist Kevin O'Neill in 1999, the series is a love letter to the world of made-up stories, posing the question of what it would be like if some of the most recognizable and unrecognizable names in fiction co-existed. Revolving around their recruitment by the British Government, the League's adventures have featured the likes of everyone from The Invisible Man and Captain Nemo to Dr. Moreau and Professor Moriarty.

"It's not just a fiction world," says Moore, "it's the fiction world. The basic concept behind the League is that every fictional story that you ever heard—even the ridiculous ones—all happened in the same world. That wasn't our intention when we started the book, but I think somewhere during the first issue when I'd realized that I'd got Robert Lewis Stevenson's Mr. Hyde having just killed Emile Zola's Nana on Edgar Allan Poe's Rue Morgue, I thought, this is good."

Following the series' first two volumes and the origin-revealing side-story The Black Dossier, Moore's latest entry, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (Vol. III): Century, centers around the advent of an apocalyptic catastrophe, told in episodes spanning three different eras of the past 100 years. Aside from its time-spanning breadth, one of most distinct elements in the new volume is the inclusion of song. The first episode, for example, which takes place in 1910, utilizes the narrative backdrop of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill's The Three Penny Opera, where the actions of the criminal "Mack the Knife" and Pirate Jenny play an integral part in the chapter's storytelling.

"It's one of my favorite pieces ever in any medium. It's astonishing," says Moore, who approached the concept with a fair amount of concern. "I was thinking, are we going to attempt to build up some kind of atmosphere and reality in this dramatic storyline and then ruin it all by having the characters bursting into song? It was a worry. But once we committed to actually doing it we found out that it doesn't make the scenes less realistic. It kind of makes them hyper-realistic. It's like having a kind of Greek Chorus that is talking directly to the reader and underlining all the emotional savagery that's going on in the main action."

Compounding the story's hyperbolized events is, once again, the art of O'Neill, someone Moore praises as being in a class of his own. "He's the equal to 18th-century satirical illustrators like Gillray and Hogarth. The warmth and the attention he brings to everyday objects and life, it's because it's exaggerated. He's not trying to be a realistic cartoonist, where this is exactly what this car looks like down to the last hubcap screw. Kevin is trying to express something. He's not afraid to go into the grotesque or the cartoonish, and I think that gives his work an incredible vitality."

With the episodes of Volume III to be released over the course of the coming year, Moore has undoubtedly established a lifeline to a genre he loves dearly, but of which he ultimately has difficulty being a part. The League makes this possible because Moore does not look at these particular stories as typical comic book fodder, but a means by which to pay homage to the great works of the past.

"Books are like that," says Moore. "They are a treasure once you've read them. You can't imagine how you ever got through your life without reading them. I don't know. I suppose in some ways The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is conceived as a kind of cultural ark, where all the bits of culture that me and Kevin care about can be stored before the deluge of shit basically rises up around our waists and swallows all of the culture that is so dear to us.

For Moore, inner creativity is constantly influenced by people and places that don't exist. "I really do think the whole of our factual culture is based upon foundations that are purely imaginary, and I think that's a wonderful thing....Art is how we extend ourselves. We create imaginary spaces, we create characters that couldn't possibly exist, and then we try to fill those imaginary spaces. We put together our personalities based upon fictional people. If they're not real, what does that make us?"