FLOOD, April 26, 2017

Several weeks ago, author Rob Sheffield was in London on assignment for Rolling Stone, invited within the venerated walls of Abbey Road by producer Giles Martin (the son of the late George Martin) to get an exclusive early listen to the forthcoming fiftieth anniversary edition of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. “Oh my god, it was so fun,” says Sheffield, recalling the experience back home in New York. “I was asking about outtakes, and Giles was like, ‘Really? You want to hear them?’ And I was like, ‘Uh, yes!’ [Laughs.] There was this amazing version of ‘[With] a Little Help from My Friends’ with Paul on piano and John on bass and George on cowbell, and [they’re] kind of figuring out what they’re going to do with it, but it sounds very, very Pet Sounds. It’s kind of amazing that this has been sitting there in a vault for fifty years and nobody’s heard it.”

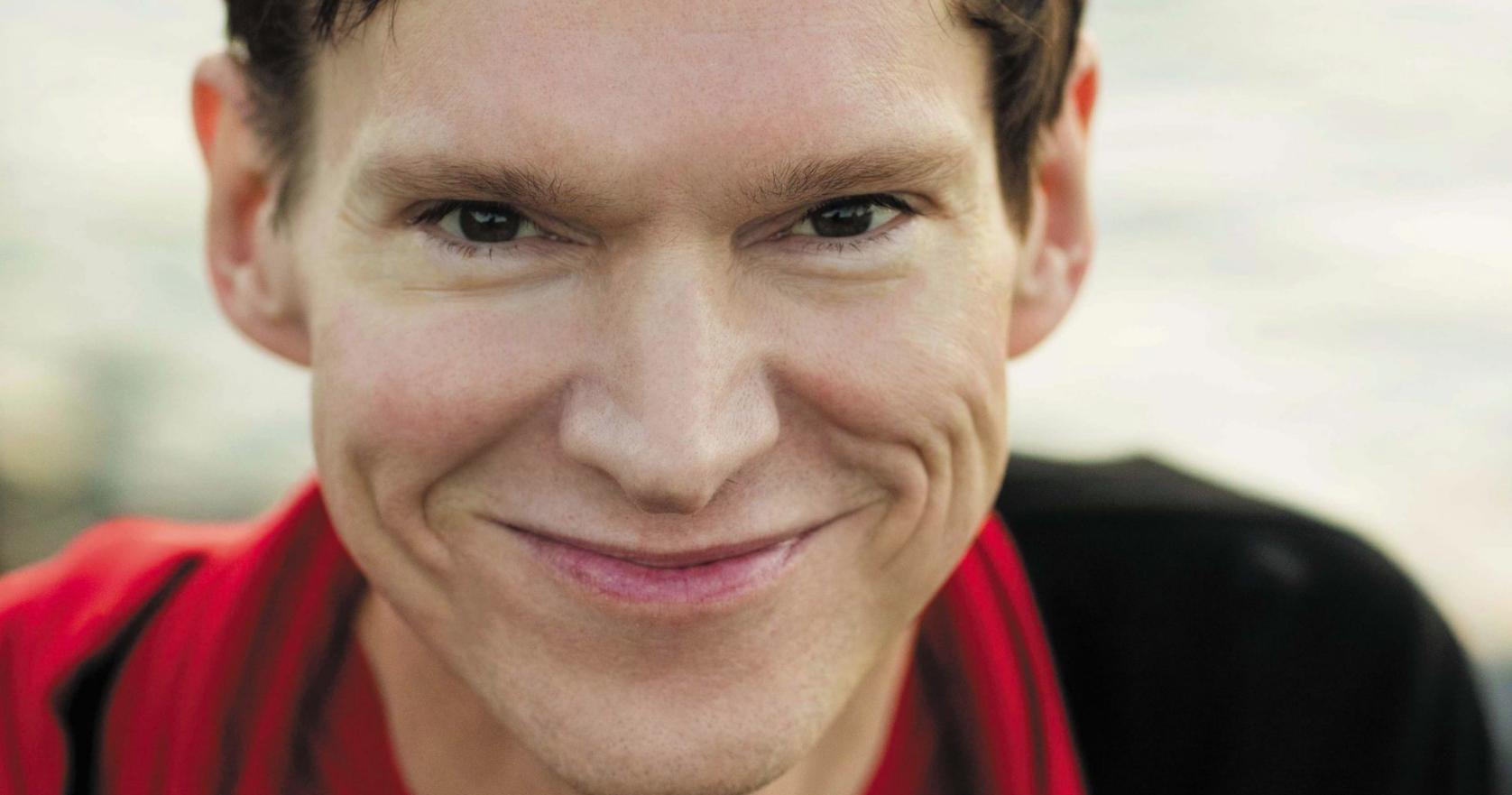

Despite his status as one of modern music journalism’s most respected writers and critics, having spent the past twenty years writing regularly quoted records reviews, three best-selling books (Love Is a Mix Tape, Talking to Girls About Duran Duran, and Turn Around Bright Eyes: The Rituals of Love and Karaoke), and as recently as last year, a literary eulogy and personal memoir examining the life and legacy of David Bowie (On Bowie), Sheffield had never once been to Abbey Road before this particular trip. As any lifelong Beatles fan would, he soaked in not just the exclusive joy of listening to previously unheard and unreleased Beatles recordings in the very studio where they were made, but also the much more common activity of recreating the foursome’s beloved Abbey Road album cover. “It’s actually hard to do the photo there because there’s a lot of traffic whizzing by,” he says. “I was like, ‘Why would anyone drive down Abbey Road knowing this is going on at any given moment?’”

By no small coincidence, the iconography of Abbey Road’s crosswalk—recreated in a minimalist black and white palette—adorns the cover of Sheffield’s latest book, Dreaming the Beatles: The Love Story of One Band and the Whole World, which somehow finds a way of striking fresh ground in some very familiar territory. Filled with essays that take on the Fab Four from a variety of angles—John and Paul’s magnetic bond as friends, rivals, and songwriters; the secret necessity of Ringo; whether Abbey Road or Let It Be is the band’s final album—Sheffield attempts to understand how this group of boys from Liverpool have continually escaped the grasp of what he calls “every era and every decade and every generation and every culture that’s ever claimed The Beatles as private property.”

Your introduction to The Beatles came through the movie Help! What do you remember from that experience?

I still remember the opening scene [with the villains] watching a film of The Beatles performing the song “Help!” in black and white, and what an astounding sight and sound it was. First, just the blending of their voices. It’s funny that it’s a song about a very adult kind of despair that a little kid isn’t going to get, but to me the way their voices played off each other, the way Paul and George sing “When…I was young” or “Now…these days are gone” [were] like they’re singing with John as he’s telling a story. You can tell John is telling a story that is very emotional to him and that the rest of the band are supporting him with that sort of teamwork. All that chemistry between The Beatles comes across so vividly in that song, and watching them do it with their matching black turtlenecks—that was just absolutely astounding to me. It was like a vision of adult life.

How would describe your relationship with The Beatles now as opposed to when you were younger?

It’s always changing. The Beatles songs that mean a lot to me at any given moment, that’s going to change from year to year. When you think of it, it’s a body of work, but it’s not a huge body of work. It’s not like Dylan or The Stones or Neil Young where there’s like hundreds of songs. There’s basically 150 Beatles songs and most of them aren’t more than three and half minutes long. And yet your relationship with that body of work changes so much over time, because the songs mean different things to you based on where you are in your life.

I probably went my whole twenties without once listening to “Strawberry Fields Forever.” It was a song I loved when I was a little boy and when I was an early teenager, but by the time I was in my late teens I was more into the earlier songs. It’s not like I ever got sour on it; I just kind of took it for granted. But then in my early thirties I was in a really miserable period, and I discovered that song as if for the first time; it became just a huge, huge personal favorite for me. It was like I was finally getting what that song is about. [It’s in] the way John sounds lost among all the instruments: There’s all these beautiful instruments all around him, the strings and the brass, and he sounds like he’s bewildered by the music surrounding him. There’s that sort of melancholy but also that very witty commentary on his own melancholy. That was something that really blew me away.

I love your comment in the book that everyone has their own private Beatles. Everyone has the song that you love but everyone else hates. You have your favorite B-side. And it really is that way. It would be very hard to find two people who share the exactly same perception of The Beatles and their work.

And for something so public, it’s really surprising. The public dimension is so high profile and yet people take it really personally.

When you were thinking about pursuing this book, was there ever a point when you questioned whether the world needed another book about The Beatles? What did you want to bring that was new to the conversation?

I didn’t want to solve the mystery of The Beatles, but I wanted to understand the mystery of why we love The Beatles so much, why The Beatles matter so much, why they stand up to the test of time over and over again in a way that no other music does and in a way no other pop culture does. To me, this is always something funny about reading Beatle books, especially Beatle books from the past, is that they always have theories that dismiss the ongoing popularity of The Beatles, or solve the ongoing popularity of The Beatles. And it’s so funny how preposterously wrong all those theories are.

It was said in the ’70s how it was nostalgia—that people missed the ’60s. That theory didn’t last very long. In the ’80s it was, “Well, something massive was happening in pop culture and The Beatles were just an echo of that. They were a mirror of their times.” And over time that theory has really fallen apart, too, because there were a lot of people in that time and in that place and there’s only been one Beatles to have emerged from that situation. It’s funny to me that the history of The Beatles is the history of us as a culture asking, “What the fuck is it with this music?” And “What the fuck is it with these four guys?” And “Why them?” And “Why these songs?” There were lots of really great bands in the ’60s and ’70s and ’80s and ’90s. Why does this band kind of lap everyone else on the track?

Did you feel like you came to, not an answer, but a personal resolution to those questions?

Not so much a resolution. But there are so many different parts to this story I wanted to understand better. Something that’s really fascinating to me is how intensely John, Paul, George, and Ringo all loved being Beatles. You can hear that on albums like Revolver and Rubber Soul and Sgt. Pepper’s; what The Beatles wanted to do with their time was hang out with other Beatles, even when they were weren’t making music and when they weren’t touring. The only other people they really related to were each other and they wanted to spend all their time with one another. All perks of celebrity are open to them, but what they really want to do is hang out together. So when John has a day off he’ll just walk over to Ringo’s and they’ll sit in the garden together. They might watch TV. But that’s what they want to do.

John has a really funny quote from 1967. He said [something like], “We always used to talk to each other in Beatle code when we were surrounded by strangers, but now that we’re not touring anymore we never have to see other people, so it’s great.” And if you listen to a record like Revolver, which is a very insular record, part of the joy of that record that makes it so powerful over time is just how madly in love they are with being The Beatles. And of course they’re competing and they’re trying to top each other and they’re taking ideas from each other, but it’s just the joy of it, you know?

During your research for the book was there anything you came across that you had never learned about the band before?

Something I came to appreciate more and more is what a turning point the [1967] death of [manager] Brian Epstein was. It wasn’t a thing where The Beatles gradually got disenchanted with being The Beatles. It turned very abruptly the weekend Brian Epstein died. Within a couple months of that, John was basically a different person.

In a great biography [of Epstein] by Debbie Geller called In My Life, another British pop manager at the time by the name of Simon Napier-Bell tells a story Brian told him that on the last American tour Brian finally fulfilled a fantasy he always had, which is that he slipped off into the audience and stood in the back in the dark where nobody could see him and he just screamed like one of the girls. That was always his deepest fantasy, to just for a moment be part of the audience and be one of the fans. There’s just something so beautiful about that to me.

You write, “They define the extremes of your memory. They’re with you when you’re just discovering music, too young to know better, and remain on top of all the other heartnoise crowding your chemistry when you’re too old for surprises.” That definitely rings true for me and it obviously rings true for you. Do you think even decades down the line from now that The Beatles are still going to be affecting people the way they are?

Well, it’s going to change. It’s always changing. It’s kind of the essence of their music. Certainly nobody would have predicted fifty years ago—there was no way of predicting then what The Beatles would mean now.

People always think it’s reached the point where it’s the end of the line: It’s time to sum up the story and what it was all about. Like with Anthology; that was very much a thing like, “OK, we’re taking stock. This is it. Finally. We’re opening the vaults and now we’re closing the vaults. That was it. Goodnight. Thank you everybody.” And then a few years later, they come out with the 1 compilation, which becomes such a massive blockbuster. It was really funny to be a music journalist at that time, just seeing the bewilderment inside the music business on every level going, “How is this happening? Why are millions and millions and millions of people buying this compilation?” Compared to Anthology, which was a labor of love that had so much work go into it, 1 was like, ‘Eh, let’s just take twenty-seven songs that are hits and put them on one CD for Christmas.” It’s yet another example of how the next phase of The Beatles story is always a surprise. There’s no end to the tale. FL