Pitchfork: November 18, 2016

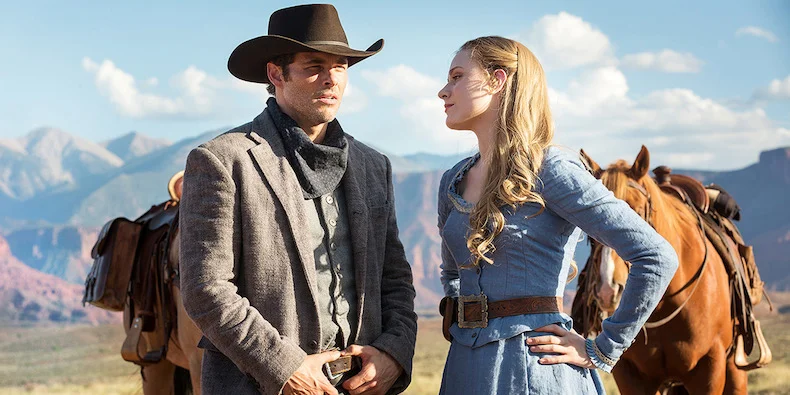

Despite spending the past several years composing the score to “Westworld,” Ramin Djawadi has never given much thought to what he’d do were he thrust into the HBO series’ titular location. Based on Michael Crichton’s 1973 sci-fi film, which imagined a consequence-free theme park where visitors could indulge in their innermost gunslinger fantasies alongside android outlaws and ranchers, “Westworld” offers a more existential interpretation of the original by focusing on the machines’ journey towards self-awareness—and the consequences that follow. “What’s interesting about the idea of a theme park like that and how it’s portrayed in the show is that it brings out the best and worst in people,” Djawadi says over the phone from his Los Angeles studio. “It’s an interesting concept, thinking of oneself being in that park and what you would do, what would you want to get out of it.”

Deep into a composing career anchored by six seasons (so far) spent scoring “Game of Thrones,” Djawadi has approached HBO’s latest prestige TV favorite with a strong sense of place and contrast. Scenes taking place in the park’s frontier landscape assume a more natural quality via acoustic guitars and percussion, while those set in the cold, glass-walled control center echo with synths and other electronics. Then there are the musical easter eggs that Djawadi arranges, and that viewers can’t seem to stop discussing, for betterand often for worse: the player piano that offers up vaguely warped renditions of modern songs like Radiohead’s “No Surprises,” Soundgarden’s “Black Hole Sun,” the Rolling Stones’ “Paint It Black,” and the Cure’s “A Forest.” “What I love about that is it just comes out of nowhere and you don’t expect it at all,” Djawadi says. “You see the settings and the way people are dressed and even though you know it’s robots and it’s all made to be modern entertainment, you would think the people in control would make everything authentic, including whatever is played on that player piano. It would be from that time period. And when it’s not, it’s that subtle reminder that, ‘Wait, there is something not right. This is not real.’ It’s just such a powerful tool that only music can do.”

Pitchfork: How were you first introduced to “Westworld” creators Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy?

Ramin Djawadi: Well, Jonah and I were working on “Person of Interest” and one day he pulled me into his office and said, “So I’m starting this new show. Would you be interested?’ And I said, “Well, what is it?” My jaw dropped when he said “Westworld” because the original movie was one of my favorites as a kid. I got so excited, thinking, “Oh my God, with that story and with Jonah’s spin on it, I’m sure it’s going to be incredible.” While we were working on “Person of Interest,” we were already talking ideas and I started writing music for it very, very early on, which most of the time I don’t do. Usually I come in towards the end during post-production when the episodes or the movie are already shot, and I get to see visuals. But this one I started writing just based on the conversations with Jonah. Then he started giving me scripts, and from that I started writing more. It was great just having that back and forth with him before there were even any visuals.

Your main “Game of Thrones” theme is among the most iconic on TV right now, and the show’s smaller musical themes follow suit from there. How did you approach the “Westworld” theme, particularly knowing it would become a standard-bearer for the rest of the show’s music?

I like to have recognizable themes and sounds that really connect to the project and that you can identify with that particular project. My goal is always, “When that theme comes on—even if you’re not in the room— you hear it and say, ‘Oh my show is starting, I gotta watch.’” With “Westworld,” the player piano plays a very important role. Jonah showed me stills of what they were planning on doing with the opening and having this robot assembly take place and actually having the robot playing the piano, and so I knew the whole piece had to be centered around that. Automatically that made it quite different for me—I could go in a totally different direction.

Let’s talk about the player piano. How did that come into play?

I have to give Lisa and Jonah full credit for that, because this is not a show where you can just drop in a modern pop song because it’s such a different genre and different show.

Why do you think these interpretations have been such a point of attention among viewers?

I’m not sure. There’s something about it. On the one hand, it’s such a minimalistic approach—most of the time it’s only on the player piano, in the “Westworld” style that [reiterates] you’re in the theme park. Then there’s the recognition factor—that they know these songs.

Or like with “Paint It Black,” you think, “Oh, that’s when Hector comes to town and there’s that big shootout.” The song just reminds you of it. Everything’s planned out [with the big scenes], including the music. It’s an event.

Aside from the “Paint It Black” set piece, the arrangements are—like you said—as bare bones as possible.

The trick is when you do these piano arrangements, you have to cover all the different elements of the track. You obviously have to cover the melody and you have to cover the harmony and what the different instruments do when there’s this full, produced arrangement. You have to somehow reproduce that in its own way with one instrument. It’s fun. I really enjoy doing it. It’s something I did when I was kid with songs in the ‘80s—pop songs and classical pieces too. It’s called piano reduction, and it’s a great way of analyzing a piece of music. That’s how I learned a lot about music.

Radiohead songs have been covered a few times. What is it with Nolan’s love of this band?

They’re just an incredible band. I myself am a huge Radiohead fan. I’m happy he’s picking those songs. [laughs]

While I’m not even that big into lyrics, their lyrics tend to be very poetic as well. I think it’s a great fit. Like with “Fake Plastic Trees”—even if you just take the title—with “Westworld,” what is real? What is not real? You can interpret it in many ways.

In some ways, prestige TV has surpassed film in its ability to tell a great story. Because these shows have become much more cinematic, accompaniments like the scores have been elevated as well. Does that factor into how you conceptualize your scores?

I totally agree with what you’re saying. There’s been a great development with scale on TV, but my approach is always the same across projects, whether it’s a video game, a movie, or a TV show, I always try to set up my sounds and my themes. I really try to stay with the characters and do the storytelling through the music. With shows like “Game of Thrones” and now “Westworld,” what’s so fantastic are the character arcs that you can’t do in two hours with a movie. With these shows, you have 10 hours just to set up the arc, so therefore with the music you can really follow that and expand upon it. It’s a great time in television and television scores.